When we first discussed linear systems theory, it was in the context of audition

where we describe an auditory signal as a single value, pressure, as a function

of a single variable, time. Linear systems theory has also been applied extensively

to vision, but there the stimulus is substantially more complicated. At a minimum,

you talk about an image (i.e., a picture,

a retinal image, a neural image) which is a function of the two spatial dimensions

x and y. But, if you are interested in temporal

sensitivity as well (e.g., to understand visual motion), then you have a signal

that is a function of three variables: x, y, and t (i.e., a movie, or sequence of images).

In audition, the basic stimulus used in linear systems theory is the sine wave.

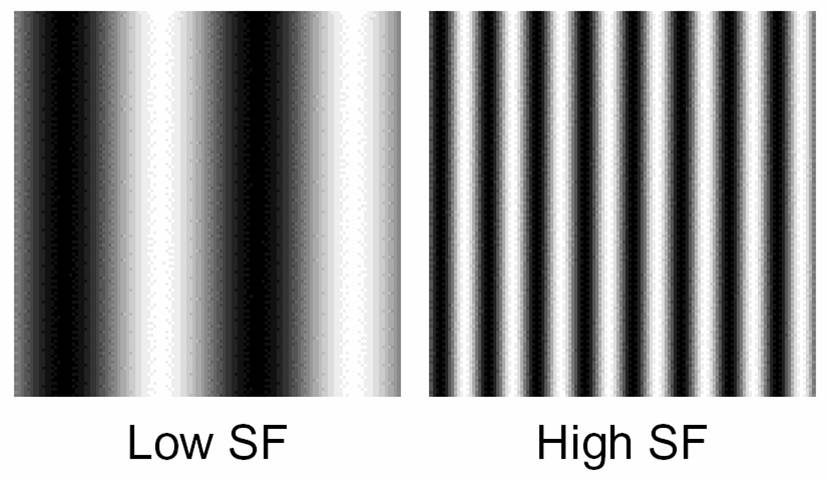

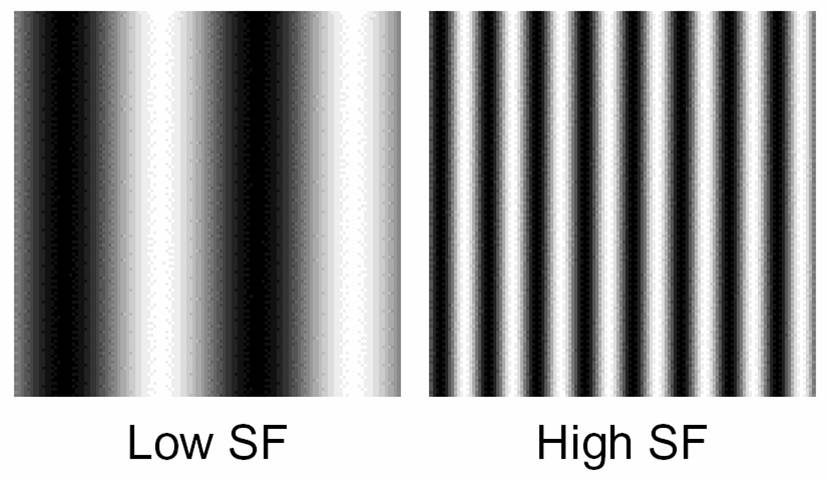

The analogous stimulus for vision is the sine wave grating. Such gratings can vary

in spatial frequency (measured in cycles/degree, for a retinal image), orientation,

phase and contrast.

Low and high spatial frequency sine wave gratings

Contrast for sine wave gratings is usually defined as Michelson contrast for which the formula is

(Imax-Imin)/(Imax+Imin) or (Imax-Imin)/(2 Imean). This is a number that ranges

from zero (the bright and dark bars have the same intensity as the mid-gray,

in other words the grating is invisible) to one (the bright bars are twice the

intensity of the mean and the dark bars are black). Note that this definition

is the same as the definition we've used previously, Weber

contrast or ΔI /

I, where ΔI means the increment of the bright

bar above the mean (Imax-Imean)

and I stand for the mean intensity

(I=Imean).

The characterization of a system in linear systems theory is the Modulation

Transfer Function (MTF), i.e., the degree to which different frequencies

are amplified or attenuated by the system. The behavioral analogy to the

MTF is the contrast sensitivity function

(CSF) which describes how sensitive an observer is to sine wave gratings

as a function of their spatial frequency. This is measured using a contrast

detection experiment wherein one determines the minimum contrast required

to detect sine wave gratings of various spatial frequencies. As usual, sensitivity

is defined as 1/(threshold contrast) (so if threshold is low, sensitivity

is high).

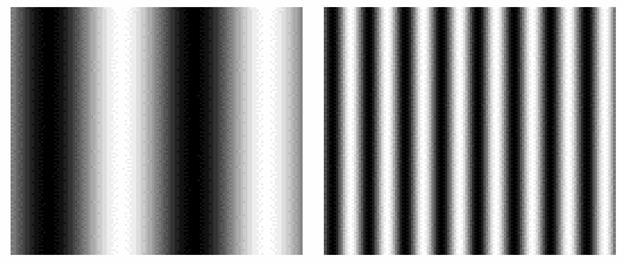

The figure above shows a pattern that increases in spatial frequency

from left to right (the bars get narrower), and decreases in contrast

from bottom to top (the bars get fainter). By tracing out the boundary

between visible and invisible you can make out the curved shape of your

CSF. The typical results of such a measurement follow:

The typical CSF is bandpass in nature. That is, you are most sensitive

for an intermediate range of spatial frequencies (around 4-6 cycles/degree),

and less sensitive to spatial frequencies both lower and higher

than this, much like the audiogram. The highest spatial frequency

you can see (the high frequency cutoff) determines your spatial

acuity, i.e., the finest spatial patterns you can see. This acuity

limit typically worsens with age.

The CSF is typically not thought of as the MTF of a single kind of neuron,

but rather an envelope of sensitivity over several underlying mechanisms,

each corresponding to neurons with differing preferred spatial frequencies

(i.e., with different sizes of receptive field; larger = lower spatial

frequency preference). A graph illustrating this follows:

In the figure above, four spatial frequency channels are illustrated, and the

notion is that the CSF represents the sensitivity pooled over those

underlying channels, i.e., sensitivity is primarily determined by

whatever channel (or set of neurons) is most sensitive to the stimulus.

Now, what does this parsing of the stimulus into different frequency

bands do for the observer?

As you can see, the low frequency filters provide information about large objects,

shadows, and other smooth, gradual changes in intensity across the image.

The higher spatial frequency filters emphasize progressively finer details.

What evidence is there for the existence of multiple spatial frequency channels?

Well, first of all, there is the physiological evidence. In V1 and beyond,

for each location in the visual field there are neurons varying in preferred

spatial frequency, orientation, direction of motion, and so on. But, there

is behavioral evidence as well. First, consider the effects of adapting

to a particular spatial frequency. One begins by measuring the CSF as illustrated

in a figure above. Then, you have the observer stare at a particular sine

wave grating (e.g., 8 cycles/degree) for an extended period of time.

The visual system adapts to that

pattern, and any neurons or mechanisms that were sensitive to that pattern

become desensitized temporarily. If one re-measures the CSF while in that

adapted state, the results are as follows:

The dotted curve represents the post-adaptation CSF and, as you can see, sensitivity

is reduced, but only for gratings with spatial frequencies near that of

the adapting grating. The idea is that the spatial frequency channels sensitive

to the adapting grating now have reduced sensitivity due to all that stimulation,

but those with spatial frequency preferences distant from the adapter remain

unaffected. Spatial frequency adaptation not only affects threshold, but

also affects the appearance of supra-threshold gratings. After adaptation

to 10 cycles/degree (i.e., even narrower bars), an 8 cycle/degree

grating will appear to have an even lower spatial frequency (even wider

bars). Likewise, after adapting to 6 cycles/degree (i.e., wider bars) an

8 cycle/degree grating will appear to have an even higher spatial frequency

(even narrower bars). The explanation is illustrated here:

The idea is that adaptation to the higher spatial frequency desensitizes

the higher spatial frequency channels (those that "see" the higher frequency

grating). Then, when you display the 8 cycle/degree grating, the center

of the response profile shifts to lower frequencies (bottom-right graph

above). When you adapt to a lower spatial frequency grating, you see the

opposite shift in the response (upper-right graph). Similar shifts happen

with orientation and direction of motion, indicating that there are channels

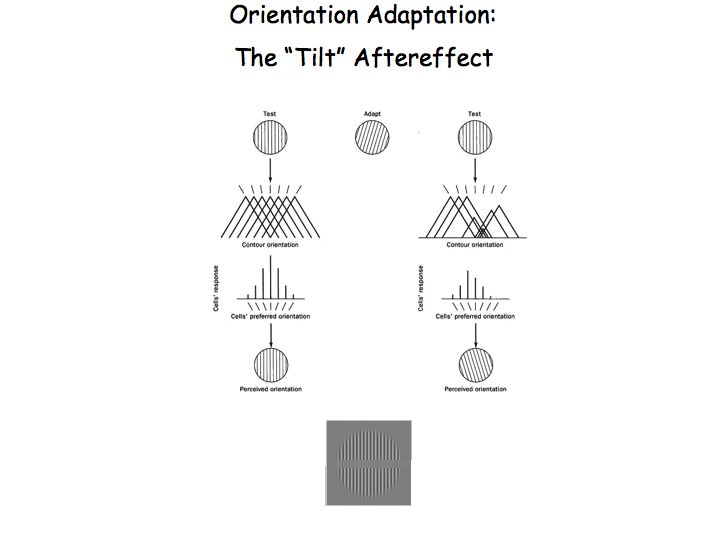

tuned for various orientaitions and directions of motion. For example, here's

an analogous explanation of the tilt after-effect based on orientation-tuned

channels. In this effect, one stares at, for example, a grating tilted slightly

top-to-the-right. After adapting, a vertical grating appears tilted slightly

top-to-the left because channels preferring leftward tilt are now responding

more strongly than those tuned to rightward tilt (because the latter were

more strongly adapted).

There are two other common methods of demonstrating the existence of multiple

spatial frequency channels psychophysically. The first is called summation.

There, the idea is that if you ask an observer to detect a combination of

two grating (literally added together on the screen), the sensitivity is

much higher if the two gratings are close in spatial frequency (so that

they are detected by the same channel) than when they are far different

in spatial frequency (so that they are detected by separate channels). A

third psychophysical paradigm is called masking. In this type of experiment, the observer

is asked to detect one test grating (with frequency f1) in the presence of another masking grating (with frequency f2). The masking grating is always present,

and the question is to what degree does it mask the test grating, making it harder to

detect. It turns out that the results lead to the same model. When the masking

grating is similar in spatial frequency to the test grating, masking is

strong, and when it is dissimilar, masking is weak. In other words, one

grating masks another only to the extent that both are detected by the same

channel.