What just happened? Light from the lightbulbs bounced off the object and into your eye. The light was absorbed by neurons at the back of your retina and a neural signal was sent off to your brain. The light coming into your eye changed over time, as the ball moved. Somehow your brain interpreted that changing array of light intensity, giving you enough information to predict the trajectory, and control your muscles to catch the ball. All of this happened in just a few seconds.

Try to imagine what it would take to build a robot capable of such a feat, using video cameras for eyes and motorized robotic arms. In fact, although there are lots of really smart people working on machine vision and robotics, we are nowhere near being able to build a robot with even modest perceptual capabilities.

We do all kinds of tasks (walking down a hallway without bumping into the walls or other people, driving, biking, crossing Broadway against the light, skiing, windsurfing, etc.) Although we usually don't think about it, these tasks involve very complex perceptual skills. Our senses must be doing a pretty damn good job.

For example, our photoreceptors respond to a single photon of light. This would be the same thing as going up on the Empire State Building, on a clear night, and if we could persuade everyone in the area to turn off their lights, we could detect the light from a single candle in Hoboken on the other side of the Hudson River.

Subjectivist view: Proponents of this view argue that there is no inherent organization to the world, but rather, our brains organize our perceptions, and we therefore believe the world is, itself, organized. But, in the face of the accuracy and precision of our senses, you must be asking, how could the subjectivist argument stand? If we are so good at detecting and discriminating physical stimuli, then surely we must be perceiving exactly what is physically there.

Gestalt psychologists - who included Wertheimer, Köhler, Wallach, Koffka, and others (most of whom emigrated to the United States before the second World War) - pointed out that our perceptions often do not simply record a stimulus.

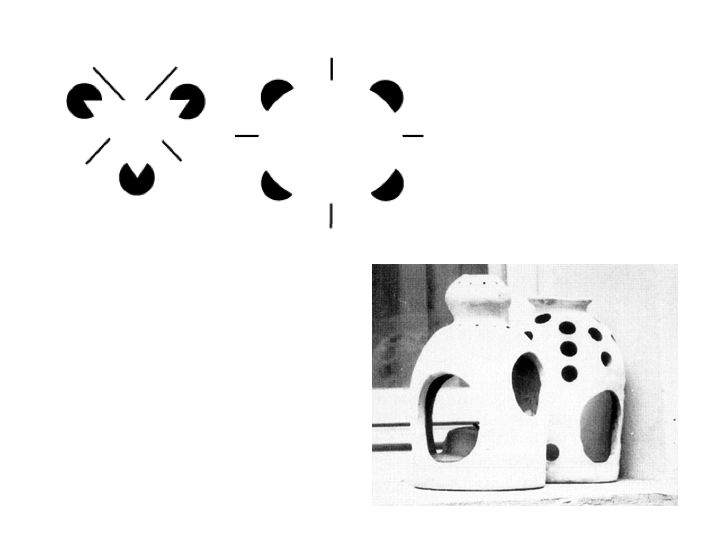

Illusory contours

Visual illusion: you see shapes (the white triangle and oval at the top) with well-defined borders. Yet, you can also probably see that the edges of the borders are not present in the image, but rather that you are inferring the existence of these borders, putting them onto the image even though they are not there. The visual system infers that there is a shape in front, occluding the black discs. Herman von Helmholtz, a great 19th century physicist, and one of the scientists who laid the foundation for modern day research on perception, called this an unconscious inference. Note that it doesn't help you to know that this is an illusion. You can't help but see it this way - that's why it is an unconscious inference - you can not consciously control or turn off the illusion.

The key point, and one that you will see repeated in this class, is that this type of filling in, this unconscious inference, this active role of your brain in seeing and also hearing, is not a special case. Much of what we perceive is an illusion; the part played by our senses is at least as important in our perceptions of the world as the part played by the world. And more generally in psychology, the part played by our minds is at least as important as the events that actually transpire.

Fraser's spiral

This looks like a spiral even though it is really a bunch of concentric circles. Again, this is an unconscious inference; even though you know it's not a spiral, you can't help but see it that way.

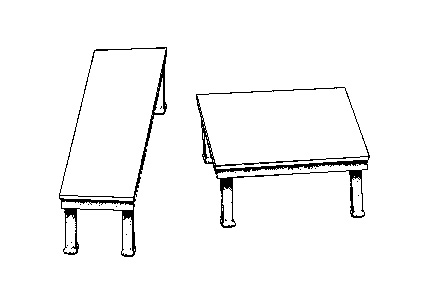

Shepard tables

Another unconscious inference. Table tops appear to be different in shape but they are actually identical. A central premise of object perception is that we see objects in a three-dimensional world. If there is an opportunity to interpret a drawing or an image as a three-dimensional object, we do. The two table tops have precisely the same two-dimensional shape on the page, except for a rigid rotation. Nobody believes this when they first look at the illusion. The illusion shows that we don't see the two-dimensional shape drawn on the page, but instead we see the three-dimensional shape of the object in space.

There are lots of other examples of visual and auditory illusions that you'll see/hear throughout the semester. There a number of good visual illusions that you can find on the internet. Here are just of few of the websites that include collections of visual illusions and demonstrations:

Synthetic view: This is the hypothesis that I am most comfortable with, and which I use as the guiding principle in my research and in the courses I teach. The world appears to us the way it does because: (1) We perceive only within the limits of our nervous system, but (2) our nervous system has evolved to reflect certain aspects of the world very accurately.

This acknowledges both of the previous viewpoints, the subjectivist and the objectivist. It agrees with the subjectivist view that our senses themselves play an enormous role in determining how we perceive the world. It also agrees with the objectivist view by claiming that our senses evolved over millions of years under constraints imposed by the world; our senses have evolved so that we can function succesfully.

The point is that the sensory systems of your brain must make some kind of inference because you do not have the opportunity to perceive the world directly. Let's say I clap my hands. You don't hear the distal stimulus, the physical event of clapping, directly. It's not like your head is sandwiched between my hands when I clap them. Rather, your ears sense the air vibrations that propagate through the room as a result of my clapping. Likewise, your eyes don't sense an object directly, as if they were rubbing up against the surface of the object. Instead, light bounces off the surface and into your eyes.

The unconscious inferences are performed by your brain. The neurons in your brain perform computations to process and transform the incoming sensory stimuli (light and sound) to make these inferences. Given the limited/indirect information available, the sensory systems of your brain do remarkably well; most of the time, the unconscious inferences are correct. Occassionally, however, these unconscious inferences fail, giving rise to perceptual illusions. By studying when and how the sensory systems fail, we can learn about how these systems work.